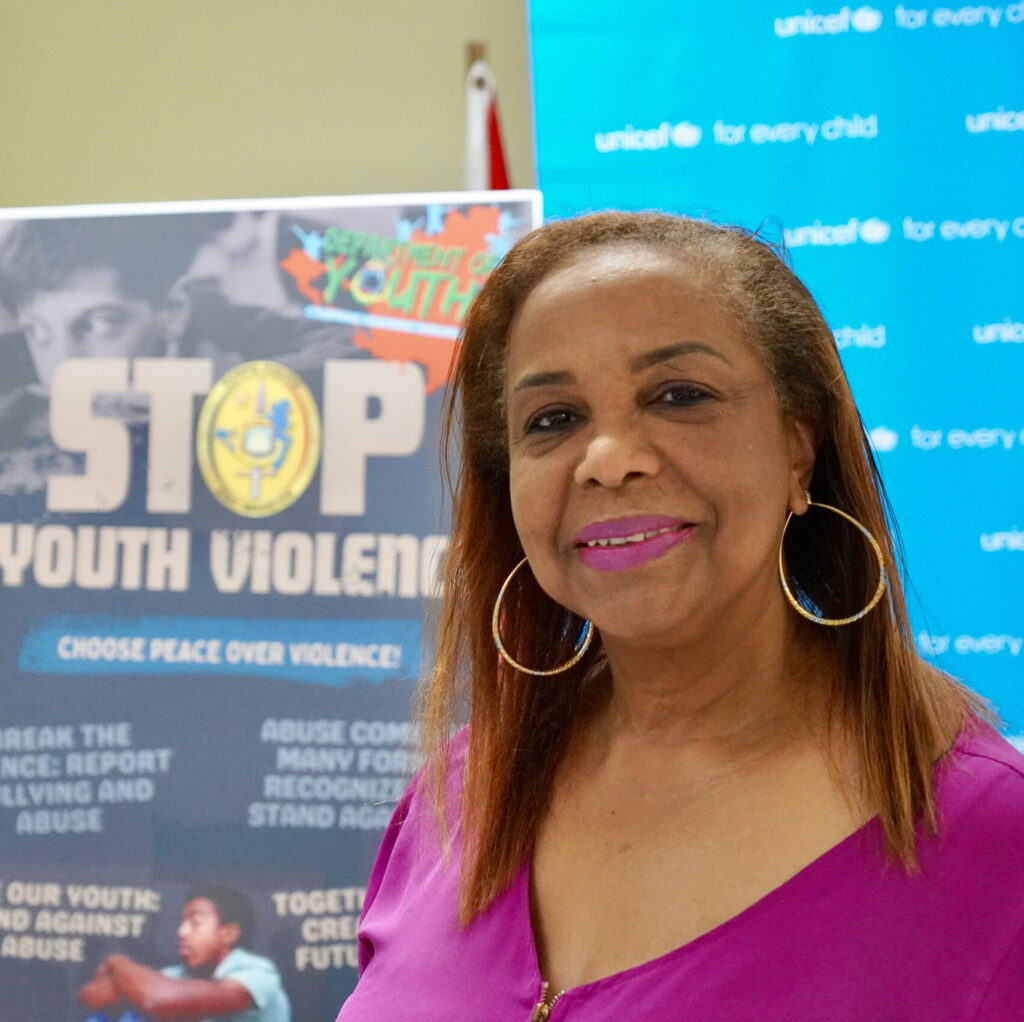

With over 20 years of experience, Dwynette Eversley has dedicated her career to addressing youth development across the Caribbean. “It’s not just about policies, but creating real change through public sector, community engagement and other support. It is about helping young people realise their full potential by providing opportunities and building resilience,” she explains.

Recently, Dwynette has assisted in developing a Positive School Connections Program (PSCP) for the Government of Sint Maarten, which empowers teachers with social-emotional learning techniques to help improve relationships with students and create safer school environments: “Teachers and other school staff participating received the programme’s pilot well; however, to solve youth violence, we need a holistic approach involving the wider community.”

Dwynette emphasises that multiple factors outside of poverty like depression, anxiety, family dysfunctionality, and experiencing violence in homes, schools and communities, can push youth toward violence.

“For many young people, violence is normalised. It’s what they see growing up.”

How has youth development progressed in the Caribbean?

In the Caribbean, youth development and participation levels still differ per country. However, we have seen the narrative changing, and youth participation is increasingly seen as central to political and social development. There is now a dynamic level of international and regional networks, which young people can access to engage with issues like food security, climate change, technology, security, economy, and sustainability, amongst other conversations.

There has also been a shift to recognise that development, particularly youth development, requires not only passion for youth work, but also an enabling environment- structure, policies, investments, tools, and networked accountability at a government level. But, governments and other agencies need to deliver the systemic support young people need to navigate challenges.

When discussing programs or policies, how do you define ‘youth’?

Globally, the definition of youth varies. The UN defines youth as individuals between 15 and 24 years old, but the Commonwealth extends this to 15 to 29. CARICOM’s definition ranges from 10 to 29. In Sint Maarten, the Youth Department defines youth as ages 0 to 24, and the Integrated Youth Policy Framework Implementation Plan provides for empowerment across those ages and stages. These variations exist because youth development isn’t strictly about age; it’s about developmental stages, life experiences, it’s the capacity to develop and enable youth agency in appropriate settings to participate in and contribute to society.

For example, research shows that youth unemployment rates are higher than national averages, especially for young women. That’s why some programs extend incentives and opportunities to persons up to age 35, as this helps balance employment access and economic participation. In first world countries, there may be a wider pool for opportunities and access, but in different Commonwealth countries experiences, for example, even at 24, many young people still need a range of supports, programmes and services for economic and social empowerment – spaces to grow, and thrive.

What have you learned from working with young people in the Caribbean?

One of the key lessons I’ve learned is the importance of offering young people the opportunity to travel and experience different cultures. It’s about providing access to the wider world beyond the confines of small islands. However, not all young people have access to these opportunities. We must remember that some face significant barriers. Those young people also need safe spaces where they can thrive, broaden their experiences and build social capital. This is a fundamental aspect of building the social and emotional intelligence that we all need.

Youth violence is a complex issue. It is violence either perpetrated, experienced or witnessed by young people.

What is youth violence?

Youth violence is a complex issue. It is violence either perpetrated, experienced or witnessed by young people. This violence can take many forms – from physical altercations to emotional or psychological abuse. It can happen in schools, on the streets, or even online.

In some cases, violence occurs between young people or between a young person and an adult, such as parents, teachers, authority figures, or others in their community. School violence, for example, includes not just physical fights among students but also verbal or psychological maltreatment from teachers, which can have a lasting impact.

Why do young people act out violently?

The reasons behind youth violence are multifaceted. Several risk factors come into play, from family dynamics to community environments. Research consistently shows that youth exposed to domestic violence, neglect, or negative peer influence are at a higher risk of becoming involved in violence. In these homes, violence is often normalised, and young people learn that aggression is the only way to deal with conflict.

Persistent poverty is another significant factor. Many young people resort to violence or criminal behaviour because they feel it’s the only way to survive. For instance, a young person might commit a robbery because their siblings are hungry, not because they want to break the law. This doesn’t mean that poverty alone causes violence, but it certainly contributes when combined with other factors like neglect or exposure to violent environments.

When do violence prevention programs work?

Violence prevention programs need to be evidence-based and targeted. There are three levels of prevention. Primary prevention programming reinforces the protective factors and competencies that youth need to form healthy relationships and make good choices. It builds confidence, communication, and empathy, among other life skills, and keeps young people engaged before any risks arise. This can be done through accessible sports, arts, after-school and leadership programmes, for example.

Secondary prevention targets young people already at risk, offering individual-level attention and support to help them navigate away from violence or behaviour that may make them justice-involved. Tertiary prevention involves working with those already in the justice system, offering psychosocial support and a range of second chances, including employability and vocational skills to help them reintegrate positively into society. To be successful, interventions must be specific. We can’t apply general solutions to complex problems.

It’s like medicine – you need the right prescription to address the ailment, not just a generic treatment.

Can you tell me more about the Positive School Connections Program (PSCP)?

Sint Maarten commissioned a report, in partnership with UWI, to investigate the prevalence of school-based violence. The report highlighted several risk factors, including poverty, lack of social support, and identified among many recommendations, the need for an intervention to lessen the violence/abuse to which primary and secondary school children are exposed.

The Positive School Connections Program (PSCP) addresses the latter risk factor, promoting social and emotional learning in the classroom. The focus is on enhancing the safety and well-being of students and educators within school settings and influencing behaviours and beliefs that strengthen a culture of safety and long-term resilience and protective factors across multiple levels. We work with teachers and students to encourage positive interactions and asset-based youth development. The program emphasises peer leadership and co-implementation, meaning young people play an active role in shaping the program. Safe spaces are crucial. Teachers and students want to feel safe. The PSCP helps create these environments by fostering dialogue and building trust within the school community.

What have educators shared about violence among young people?

Educators have expressed concern about how normalised violence has become, not just among students but also among parents. Many parents take a zero-tolerance attitude toward violence, but they may also justify it as a way of solving problems. This normalisation of violence makes it challenging for schools to create safe, nurturing environments. Teachers have also noticed that many children lack empathy and affection, which are essential to healthy development.

When children don’t feel loved or cared for, they struggle to connect with others and may display aggressive behaviours.

And how did participating young people weigh in on this topic?

When we asked young people about violence, their responses varied depending on their school and personal experiences. Some described their environment as violent—talking about hearing gunshots or witnessing fights on their way home. Some students also mentioned instances of emotional mistreatment by adults in the school system. Some reported it, but others didn’t, indicating the need for more robust support structures.

Additionally, most students were unaware of their own potential as change agents using the medium of school or youth councils or formal youth networks. In only one or two schools, students had systems like prefects, which functioned more for discipline than support. There was a clear call for better youth networks.

What will determine the success of violence prevention initiatives?

The success of the PSCP, or any youth violence prevention initiative, will depend on having a clear agency responsible for oversight. This should not be the police, as globally, young people will not naturally want to work alongside the police, nor will our police systems have the capacity for such social development. The agency, such as an assigned department in Government, should be equipped to build and execute programs that engage parents, community leaders, and credible messengers who can connect with young people – and young people themselves.

We also need to provide more counselling and psychosocial support. The level of need is high, and without addressing the underlying psychological issues young people face, we won’t see meaningful change. Lastly, but as notably, there should be functioning youth platforms, such as youth bodies in schools or, ideally, a national youth council, that empower young people to participate in conversations, community action, and decision-making.

empower young people to participate in conversations, community action, and decision-making.